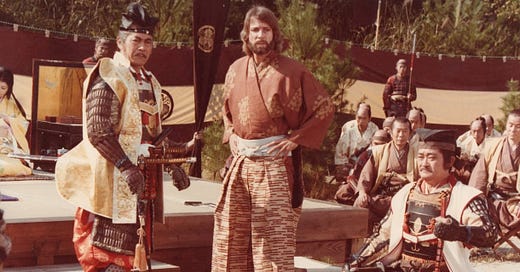

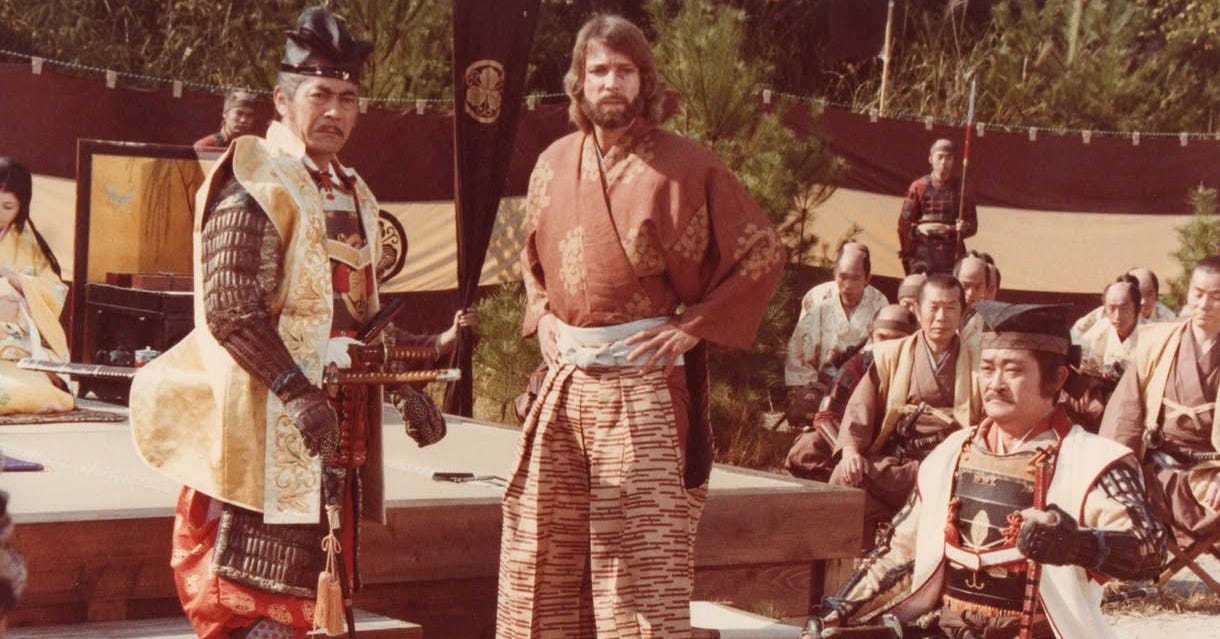

SYNOPSIS: In 1598, English pilot John Blackthorne (Richard Chamberlain) sails a Dutch ship to Japan. By embracing Japanese culture he becomes a high ranking aide to warlord Yoshi Toranaga (Toshiro Mifune) and fights other warlords, dastardly Jesuits, and his own inability to learn more than like ten words in Japanese, while pursuing a doomed romance with married noblewoman and only person patient enough to translate for him, Toda Mariko (Yoko Shimada). Let this be your reminder that “I don’t speak [language]” and “What is this called?” are the most important four-word phrases to learn in any language.

James Clavell’s Shōgun was a cultural phenomenon in the early 1980s. One of the most successful TV miniseries of the decade, it drew tens of millions of viewers and won the Emmy and Golden Globe for Best Limited Series. I remember watching it on recorded VHS with my mom when I was about kindergarten age. She was in love with Richard Chamberlain (don’t tell my dad), and a devoted reader of James Clavell.

Clavell’s semi-autobiographical novel King Rat (1962) tells the story of Allied prisoners in a Japanese POW camp during World War II. My mom, who was Indo-Dutch, had lived through a similar experience: as a child, she was interned with her mother and older brother in a Japanese concentration camp in Indonesia, while her father was sent to a labor camp in Thailand. They were reunited after the war. Perhaps not coincidentally, despite these harrowing experiences, both Clavell and my mom developed a lasting fascination with Japanese culture.

Clavell wrote the novel Shōgun in 1975 as the third installment of his six-part Asian Saga. At 400,000 words—released in two volumes of about 600 pages each—it was a swashbuckling bestseller. The main characters are all based on historical figures: John Blackthorne on the Englishman William Adams (1564-1620), who also sailed to Japan and ended up a samurai; Toda Mariko on Hosokawa Gracia (c. 1563-1600), a Japanese noblewoman and Christian convert whose violent death helped unify Japan; and Yoshi Toranaga on Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616), who became the first in a line of shōguns, giving his name to a dynasty that lasted two centuries.

Before turning to novels, Clavell had a successful screenwriting career; his credits include The Fly (1958), The Great Escape (1963), and To Sir, with Love (1967). His writing instincts were cinematic, and he had a clear vision for how Shōgun should look on screen. A lavish joint venture by NBC, Japanese film studio Toho, and national broadcaster Asahi, Shōgun originally aired over five consecutive nights in September 1980, clocking in at roughly 7.5 hours of screen time, not counting commercial breaks. An abridged theatrical cut was released in U.S. theaters that November. The casting of very-American Richard Chamberlain as very-English John Blackthorne was a bit of a stretch (Clavell reportedly wanted Sean Connery; Roger Moore and Albert Finney were also considered), but ultimately a savvy choice. Chamberlain, who passed away just this week at age 90, was the undisputed king of the romantic TV miniseries—and caused many a suburban mom to swoon, my own included.

My Review

As I mentioned in my review of Return of the King, not a lot makes sense when you’re a child, so nonsensical or bad creative decisions tend to just wash over you. Revisiting Shōgun as an adult, however, I am both amazed my mom let me watch this, and struck by how much time the series devotes to keeping the English protagonist comfortable. Two of the areas in which this plays out are the way the series handles language, and its treatment of female characters. The result is a Japan that feels accessible, but flattened — especially in how the series renders Japanese women as emotional translators and sexualized guides through a world Blackthorne doesn’t (and really doesn’t need to) fully understand.

Much of the miniseries centers on Blackthorne’s struggle to understand and speak Japanese — aided, most notably, by the beautiful and poised Mariko. He first meets her as an interpreter, since he doesn’t trust the scheming Jesuit Father Martin Alvito (Damien Thomas) to translate his words accurately. In a screamer of a plot point midway through, the villainous samurai Yabu (Frankie Sakai) makes the entire village responsible for teaching Blackthorne Japanese in six months, on pain of death. Blackthorne’s response to this is to protest the cruelty of the demand, rather than to, you know, learn Japanese (you could do both, though?).

In Clavell’s novel, language dynamics are far more nuanced. There are many scenes between Japanese characters when Blackthorne isn’t present, and these allow for richer development — both of character and cultural perspective. Japanese characters speak to each other in Clavell’s English prose (decorated with some cringey Japanese-isms, so you remember it's not really English), allowing them the opportunity to mock foreigners’ language skills, eating habits, and/or genitalia, as the case may be. The book gives its Japanese characters interiority. The miniseries mostly gives them silence.

The two Japanese leads (Mifune and Shimada) spoke little or no English, and Shimada mainly delivered her English dialogue phonetically, an impressive feat. But for scenes between Japanese characters, the filmmakers chose not to provide subtitles, opting instead for long stretches of untranslated dialogue (YouTube’s super helpful caption was often [speaking foreign language]). When these scenes became narratively unavoidable, they reached for a truly baffling solution: the omniscient narrator, Orson Welles, says their lines, sometimes while doing an impression of them. This is precisely as ridiculous as it sounds, particularly whenever he voiceover-growl-shouts Toshiro Mifune’s lines. Let the man growl-shout for himself!

Later in the series, Blackthorne has supposedly learned enough Japanese to follow conversations, but the non-translation persists. Was the idea that American audiences wouldn’t tolerate subtitles in prime time? Were the producers unwilling to dub, even though they clearly did so for some of Shimada’s more difficult English lines? Whatever the rationale, the result is the same: Japanese characters are sidelined, and for a series about cultural exchange, it leaves the viewer feeling like they’re missing half the conversation — because they literally are.

That same flattening of perspective also shapes the way the series portrays Japanese women. As in the novel, they’re presented mainly as submissive, refined, gentle — and sexually available, a stereotype that wasn’t great then and certainly hasn’t aged well. Reviewing Shōgun at the time, historian Henry Smith primly remarked that “The daimyo ladies of sixteenth-century Japan were strictly sequestered and rarely had the chance to meet any men other than immediate family. Nor can one imagine any Japanese woman of good breeding entering the bath so casually with another man — let alone a ‘barbarian,’”1 referring to a steamy scene in which Mariko plunks herself into a hot tub with Blackthorne. This doesn’t entirely jibe, however, with accounts by contemporaries like the Jesuit Luís Fróis, who was astonished that Japanese women were “free to go where they please without their husbands’ knowledge.” While such accounts were long discounted by historians as orientalist exaggerations, many historians now accept them as fairly accurate, at least in the pre-Tokugawa period shown in Shōgun. Fróis also described Hosokawa Gracia, the historical figure on which Mariko is based, as having “the mind of a monster” but in a good way - “a woman who surpassed her nature.”2 But in the series, whether they’re speaking Japanese or lounging in a bath, Japanese characters (and particularly Japanese women) exist mainly to teach Blackthorne a lesson — linguistically, spiritually, and occasionally erotically.

The miniseries also aired in Japan, to initial curiosity and then terrible reviews. The Japanese national broadcaster Asahi hedged its bets by having Shimada and former ambassador Edwin O. Reischauer record a statement asking for the audience’s patience with the show’s errors and inadequacy, which seems like, yeah, they knew what they were doing.3

Sundry other observations, in no particular order, including a couple of bright spots:

Production value. NBC was looking for a prestige epic, and they got one. The film was shot on location and in studio in Japan. Himeji City served as Anjiro, where Blackthorne comes ashore and spends much of his time, and the show also includes exterior shots of Himeji Castle and Hikone Castle. The lush score by Maurice Jarré feels dated now, but at the time this was peak epic film signaling. The costuming, set design, and weaponry all feel first rate, and the ships are also incredibly impressive — Blackthorne’s ship Erasmus was a borrowed full scale reconstruction of Sir Francis Drake’s Golden Hind, but there’s also a Japanese galley prominently featured, and it all looks great.

Nobody tosses a Portuguese pilot. I literally did a double take at an extremely young, non-dwarven John Rhys-Davies as Rodrigues, the Portuguese pilot of the Black Ship (which engaged in the annual triangular trade of South American and Japanese silver for Chinese silk through the port of Macau, facilitated by Jesuits). His performance, which is just as shouty as Gimli but with 100% less facial prosthetics, also very much reminds me of famed high winds actor Matt Berry in Toast of London.

Let Mifune cook. Despite the aforementioned questionable choice not to subtitle, Toshiro Mifune is still in a league of his own here. Kagemusha was released a month after Shōgun aired, but Mifune never made another film with Kurosawa after Akahige (1965) because they got in one of the fights for which the director was famous. Both these 1980 movies might have looked very different if they hadn’t. Even just standing there, glaring with his trademark divine impatience, he faces down assassination attempts, earthquakes, and Richard Chamberlain literally prancing around the set. It’s like the miniseries is just something that’s happening to other, lesser, people. He doesn’t need subtitles. He doesn’t even need dialogue.

My Study Abroad from Hell. Blackthorne’s surviving Dutch shipmates have a terrible time in Japan. Unlike Blackthorne, who notionally learns Japanese (though Mariko continues to translate for him right up to her untimely death since, no subtitles), they stay secluded, eating no Japanese food, learning no Japanese, and engaging with no Japanese culture. As a result, they are lice-ridden, miserable, and borderline unhinged by the time Blackthorne gets back to them, just like that group of kids during your year abroad that didn’t ever leave their apartment and just ordered McDonald’s.

Small rant: bad hair. Though costuming was gorgeous, the obligatory samurai head-shave/ ponytail combo did not look good in this production. It’s a tough look to pull off anyway, but when you put your actors in swimming caps, wigs, and forehead pancake makeup instead of actually shaving their heads it looks way worse. For something with such high production value otherwise, it was weirdly cheap-looking. Kurosawa just made people shave their heads. It grows back.

In conclusion: as a child of the ‘80s I have a soft spot for the miniseries format, and I think it’s because it is finite. No never-ending, shark-jumping shows, just a long-form, coherent story that ends before the audience gets bored; despite Shōgun’s many flaws, it achieves this. I haven’t had time to watch the new Hulu/ FX Shōgun yet, but it sounds like it fixed a lot of the problems I had with this one, so I’m looking forward to it. But they’ve also approved it for two more seasons, so now I’m not so sure…

Henry Smith, “Reading James Clavell’s Shōgun,” History Today (October 1981), 39-42, 40.

Quoted in Mark Hudson, Europe and the End of Medieval Japan (Arc Humanities Press, 2024), 60, 61. On women in sixteenth-century Japan, see Haruko Ward, Women Religious Leaders in Japan’s Christian Century, 1549-1650 (Ashgate, 2009).

Paul Bernstein, “Making of a Literary Shōgun,” New York Times September 13, 1981